Arthritis Explained: What’s Happening Inside Your Joints

Essential Points:

Arthritis isn’t just aging—it’s a joint-disrupting condition that can lead to pain, stiffness, and serious balance issues, making falls more likely as we grow older.

Osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis damage joints in different ways, but both contribute to instability by weakening muscles, impairing proprioception, and triggering inflammation.

Early diagnosis, targeted exercise, weight management, and joint-friendly strategies can significantly slow arthritis progression and reduce your risk of falls and long-term disability.

If you’ve ever felt stiffness in the morning or aching joints that just won’t quit, you’re not alone, arthritis affects almost 1 in 4 adults in the United States. (1) Maybe your knees feel creaky when you stand up. Maybe your fingers are a little less nimble than they used to be. Or maybe you've just chalked it up to "getting older” like the majority of us do.

But arthritis is more than just a nuisance or a natural part of aging, it’s a condition with real consequences that can dramatically affect your quality of life. And more importantly for readers of Science of Falling, arthritis can be a large contributor to balance problems and fall risk as we age. (2, 3, 4) I see it firsthand in my patients on a daily basis.

Why? Because when your joints hurt, you move less. When you move less, your muscles weaken, your proprioception dulls, and your reflexes slow down and lose some steam. All of this sets the stage for instability, near-accidents, and eventually even preventable falls.

So, let’s pull back the curtain.

What’s actually going on inside an arthritic joint? Why do some people get it in one knee, while others feel it in their hands, hips, or spine? And what’s the difference between the "wear-and-tear" type of arthritis and the kind that seems to attack your body from the inside?

This article will walk you through what we in the medical field call the pathophysiology of arthritis in clear, simple terms. We’ll explore how it develops, what it does to your joints over time, and why understanding this process can help you take back control. Whether your goal is to stay active, avoid future falls, or just get through your day without that deep, aching discomfort, you’ll understand yourself and your joints much better.

Let’s start with the basics.

Normal Joint Anatomy and Function

To really understand what arthritis does to your body, it helps to first know what a healthy joint looks like and how it functions. A joint is defined as a region where two bones contact each other. (5) Think of them as finely tuned machines that are complex, elegant, and designed for smooth, pain-free movement. When all parts are working in harmony, you hardly notice them. But when something goes wrong, every step, reach, or twist can become a painful reminder that something’s out of sync.

Let’s take a quick tour of the key players inside your joints, so you can better appreciate what arthritis disrupts and why movement starts to hurt.

Articular Cartilage: The Literally Smooth Operator

This is the glossy, white tissue that covers the ends of bones where they meet at the joint. (6) Articular cartilage is made of a specialized type of connective tissue that’s incredibly smooth and resilient. Its job is twofold:

Cushioning: It absorbs impact every time you walk, run, jump, or even just stand up.

Friction reduction: It allows bones to glide over one another with minimal resistance.

In a healthy joint, cartilage is like a well-oiled ice rink, it lets everything slide with ease. But this tissue doesn’t have its own blood supply, which means it doesn’t heal well once damaged. (6) That’s part of what makes arthritis, especially osteoarthritis, so stubborn and progressive once it begins.

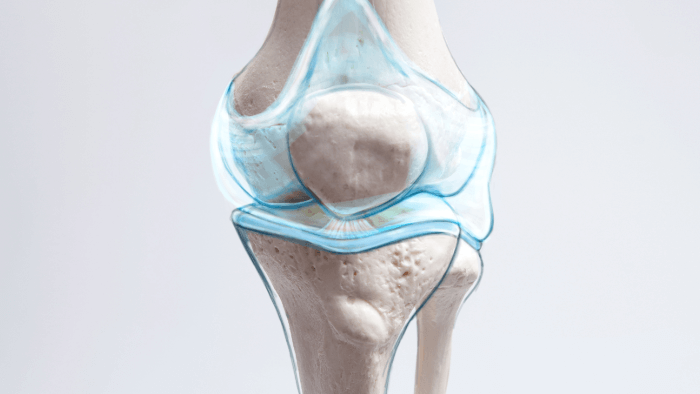

Synovial Membrane and Fluid: The Joint’s Lubrication System

Encasing the joint is the synovial membrane, a thin lining that produces synovial fluid, a slippery substance that lubricates the joint and delivers nutrients to the cartilage. (5)

Synovial fluid keeps everything moving smoothly, kind of like motor oil in an engine.

It also plays a crucial role in reducing friction and wear over time.

When inflammation hits, as it often does in rheumatoid arthritis, the synovial membrane can become thickened and overactive, flooding the joint with inflammatory chemicals that break down cartilage and cause swelling and pain. (7) This inflammation of the synovial membrane is called synovitis.

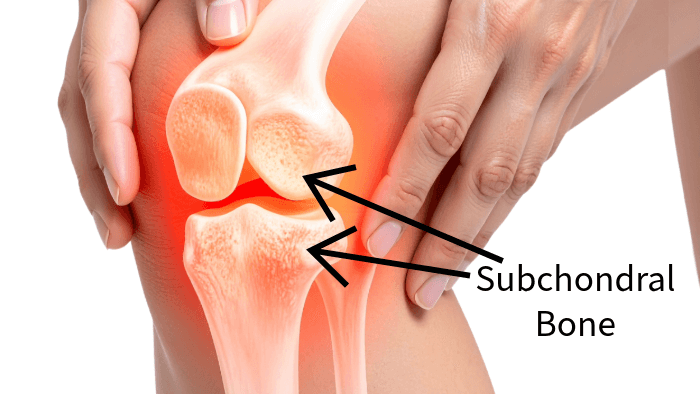

Subchondral Bone: The Foundation Layer

Beneath the cartilage lies the subchondral bone, a dense layer that supports the overlying cartilage and absorbs shock. (8)

This bone layer acts like a shock absorber in your car, sturdy but flexible enough to take the hit when your foot strikes the ground.

It helps distribute mechanical stress evenly through the joint.

When cartilage thins or disappears (as it does in OA), the subchondral bone often responds by becoming thicker and denser, a change called subchondral sclerosis. (8, 9) This may sound like a good thing, but it actually leads to stiffer joints and more pain, as the bone loses some of its ability to flex under pressure.

Ligaments, Tendons, and Muscles: The Joint’s Support Team

No joint works in isolation. A healthy joint relies on a network of soft tissues to stay stable and move correctly:

Ligaments connect bone to bone, keeping the joint aligned.

Tendons connect muscle to bone, transmitting the force needed for movement.

Muscles surrounding the joint provide dynamic support, reacting to movement and helping protect against injury.

In people with arthritis, pain and inflammation can lead to muscle inhibition, where the muscles around the joint don’t activate properly. This can be especially seen with the quadriceps in knee arthritis. (10, 11) This weakens the support system, potentially accelerating joint degeneration and increasing the risk of falls.

Why This Matters

When everything’s working as it should, your joints allow you to move through life with ease, whether you're going for a walk, dancing in your kitchen, or playing with your grandkids. But when arthritis strikes, it’s like throwing a wrench into a finely balanced system.

Cartilage breaks down

Inflammation invades the synovial lining

Subchondral bone stiffens

Supporting muscles and ligaments weaken

Understanding what’s going wrong at this structural level helps us not only grasp why arthritis hurts but also guides us in finding better ways to manage it, from medications and exercise to joint replacement or regenerative therapies. In the next few sections, we’ll home in on exactly how arthritis develops and progresses, what’s happening at the cellular and chemical level, and why catching it early (or even better, preventing it) can be life-changing.

What is Arthritis?

At its core, arthritis is a term that simply means inflammation of the joints, but that definition doesn’t quite capture how complex or varied it really is. There are over 100 different types of arthritis, each with its own triggers, symptoms, and long-term consequences. (12) Some forms are purely mechanical, while others are driven by immune dysfunction. Some come on slowly and quietly over the years, and others seem to appear overnight. What they all have in common is this, they compromise your joints.

Here’s how arthritis shows up in most people (13, 14):

Joint pain and stiffness, especially after periods of rest due to decreased lubrication

Swelling or warmth around the joints

Reduced range of motion or joint deformities

Difficulty with movement, walking, or daily tasks

In more aggressive types, fatigue and systemic inflammation

Arthritis and Aging Populations

By the time people hit their 60s, its estimated that over 50% of people report some for of arthritis. (15) It’s one of the top causes of disability in older adults, and the link between arthritis and falls is no coincidence. The CDC estimates that adults with arthritis are more than twice as likely to report a fall injury in the past year compared to those without it. (16)

In other words, this isn’t just about aches and pains. It’s about your ability to live independently, maintain your balance, and move with confidence into your later decades.

Now lets get into the weeds of how arthritis actually breaks down your joints from the inside out by looking at two of the most common types, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Osteoarthritis: The “Wear-and-Tear” Model

Osteoarthritis (OA) is by far the most common form of arthritis, especially in older adults. (14) It affects an estimated 33 million Americans, and that number is expected to significantly rise as the population ages. (17) You might hear people call it “degenerative joint disease”, and that’s a pretty good description of what it is, a general degeneration of the joint over time.

In fact, many doctors may tell you your joint pain is just “wear and tear” and comes with age. But that phrase can be a bit misleading. It makes OA sound like a passive, inevitable part of aging, when in reality, it’s a dynamic and degenerative process that affects more than just cartilage, and isn’t always a normal part of aging.

So, let’s break down what’s really happening inside the joint when osteoarthritis manifests, and why it matters for your long-term mobility and fall risk.

What Triggers Osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis often develops over time, and while aging plays a role, it’s far from the only cause. In fact, younger adults can develop OA too, especially if they’ve had a joint injury or overuse from repetitive movements.

Here are the most common initiating factors (18):

Mechanical stress: Repetitive loading (think years of kneeling, lifting, or high volume running) gradually wears down the joint when not properly balanced with rest and recovery.

Aging: As we age, cartilage loses its elasticity and shock-absorbing qualities.

Genetics: Some people are more predisposed due to inherited joint structures or biochemical profiles.

Obesity: Extra body weight places increased force on weight-bearing joints like the hips and knees.

What Happens Inside the Joint? (Pathophysiology of OA)

Let’s go back to that healthy joint for a moment. In a normal joint, the cartilage cushions the bones and allows for frictionless movement. In osteoarthritis, that system slowly breaks down:

Cartilage Breakdown

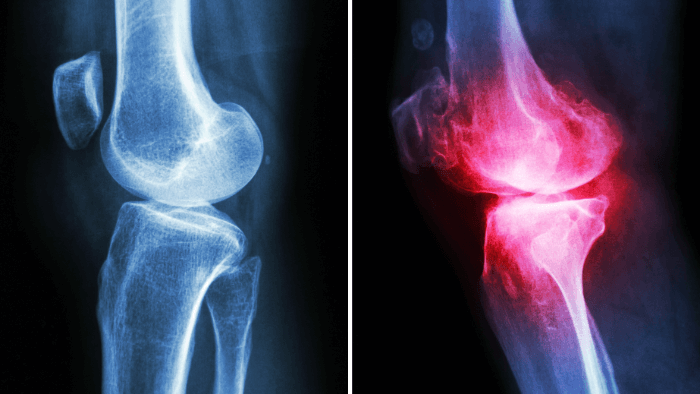

The process usually starts with cartilage softening and developing small fissures (cracks). (19) Eventually, it wears away entirely, leaving the underlying bone exposed.Bone-on-Bone Contact

Without the cushion of cartilage, bones contact each other directly. This causes pain, stiffness, and inflammation.Subchondral Bone Remodeling

In response to stress, the bone underneath the cartilage becomes sclerotic, denser and less flexible. (20, 21) It may also form osteophytes (bone spurs), which can further limit movement and irritate surrounding tissues.Low-Grade Synovial Inflammation

Although OA is not primarily driven by the immune system, the joint still becomes inflamed (a immune system driven reaction to injury). (22) This low-grade inflammation contributes to joint swelling, pain, and the breakdown of surrounding structures over time.Reduced Joint Space

On X-rays, OA often shows up as narrowing of the joint space, a sign that the cartilage is essentially gone. (23) Less space means more stiffness and less freedom to move.

Symptoms of Osteoarthritis

Not everyone experiences OA the same way, but common symptoms include (18, 24):

Aching joint pain that worsens with activity

Morning stiffness (usually lasting less than 30 minutes)

Clicking, grinding, or popping sounds (crepitus)

Swelling and tenderness

Reduced range of motion

Joint deformities in advanced stages

OA often affects weight-bearing joints like the knees, hips, and spine, as well as the hands. (25) And unlike rheumatoid arthritis (which we’ll get to next), OA tends to be asymmetrical, you might have it in one knee but not the other.

Why OA Matters for Fall Risk and Mobility

It’s easy to shrug off a bit of knee pain, but the consequences of OA go beyond discomfort. When your joints don’t work properly, it affects how you move, subtly at first, then more dramatically as time goes on.

Here’s how osteoarthritis can increase your risk of falling:

Altered gait mechanics: Due to pain, reduced range of motion, and uneven joint loading people with OA may have altered walking form.(26, 27) This can lead to greater overall instability and balance deficits.

Altered Muscle Activation: Pain inhibits full muscle engagement, both consciously and unconsciously, leading to strength loss over time, especially in the quadriceps and glutes. (28, 29, 30, 31)

Reduced joint proprioception: The brain can become less “aware” of the joint position in space leading to reduced balance ability. (32, 33)

Fear of movement: Many people with OA subconsciously limit their activity to avoid pain, leading to stiffness, weakness, and reduced confidence in movement. (34, 35, 36)

In short, OA can set off a vicious cycle:

pain → less movement → weaker muscles and stiffer joints → greater fall risk.

But the good news is that early intervention makes a huge difference. Targeted exercise, weight management, supportive footwear, and mobility training can significantly slow progression and restore quality of life.

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): The Autoimmune Assault

While osteoarthritis wears away the joints from the outside in, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) attacks from the inside out. It’s a whole different beast, and a much more aggressive one. It’s a form of arthritis I am all too familiar with as my wife suffers from RA.

RA is a chronic autoimmune disease, meaning your immune system mistakes your own joint tissue for a foreign invader and launches a full-scale inflammatory attack. (37) The result? Swelling, pain, fatigue, and long-term joint destruction if left untreated.

Let’s look inside the joint to understand how this autoimmune assault unfolds.

The Biology Behind RA (Pathogenesis)

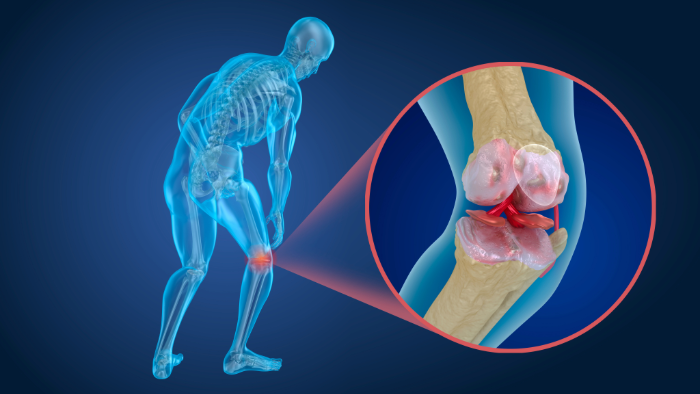

Immune System Malfunction

For reasons we still don’t fully understand, the immune system targets the synovial membrane, the thin lining that surrounds each joint. (38)Synovial Hyperplasia (Pannus Formation)

This immune attack causes the synovium to become thick and inflamed, forming a structure called pannus, an overgrowth of tissue that invades and erodes cartilage and bone. (38, 39)Enzyme and Cytokine Release

The pannus releases destructive enzymes, like matrix metalloproteinases, along with inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha and interleukin-6 (IL-6). (40) These substances don’t just break down joint tissues, they also contribute to systemic inflammation throughout the body.Bone and Cartilage Destruction

Over time, the joint becomes deformed and unstable. (41) Ligaments stretch, bones erode, and joints may partially dislocate or become permanently misaligned.

Recognizing Rheumatoid Arthritis

RA is notorious for being sneaky in its early stages. It might feel like a bad flu or vague joint pain at first. But it usually becomes more distinct over time.

Here’s what to watch for (42):

Symmetrical joint pain: Unlike OA, RA typically affects joints on both sides of the body (e.g. both wrists or both knees).

Morning stiffness lasting longer than 30–60 minutes

Swollen, warm, and tender joints: especially in the fingers, wrists, elbows, and knees.

Fatigue, low-grade fever, weight loss: systemic inflammation affects the whole body.

Progressive joint deformities: like ulnar deviation in the hands or joint subluxations.

Flare-ups and remissions: Symptoms can worsen suddenly and then calm down for a while.

RA can appear at any age, though it most commonly shows up between ages 30 and 60. (42) Women are affected about three times more often than men.

RA, Frailty, and Fall Risk

RA isn’t just about sore joints. It’s a systemic disease, meaning it affects your whole body, including the cardiovascular system, lungs, and even mental health. (43)

And when it comes to falls and functional decline, RA can be a perfect storm:

Muscle wasting and weakness: Chronic inflammation leads to a condition called rheumatoid cachexia, where muscle mass is lost even if you're eating enough. (44)

Balance issues: Pain and joint instability can make it harder to stay upright. (45, 46)

Cognitive Dysfunction: RA can lead to cognitive dysfunction reducing overall mental capacity and attention in part due to pain, poor sleep, and fatigue. (47)

Medications: Some drugs used to treat RA, like corticosteroids, can weaken bones (raising fracture risk) or cause dizziness. (48)

Over time, people with poorly managed RA often experience reduced physical activity, social isolation, and even depression, all of which further undermine balance, confidence, and independence.

OA vs RA In a Nutshell

While both osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis lead to joint pain and reduced mobility, their causes, progression, and treatment strategies are very different.

Here is a quick comparison chart:

Understanding the difference can help you, and your healthcare provider, make more informed decisions about treatment, exercise, and fall prevention strategies.

Beyond the Big Two: Other Forms of Arthritis You Should Know

When we talk about arthritis, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis tend to steal the spotlight, and for good reason. They're the most common and have the greatest impact on mobility and long-term health. But they’re not the only players in the joint-pain game. There are other, less common types of arthritis that still deserve a moment of your attention, especially because they, too, can affect your balance, mobility, and fall risk.

Let’s take a quick walk through a few noteworthy types:

Gout: The Crystalline Villian

If you’ve ever woken up with intense pain in your big toe, gout might be the culprit.

Gout is a form of inflammatory arthritis caused by a buildup of uric acid crystals in the joints. (49) This build up is often due to dietary choices such as high red meat consumption. While it’s often thought of as an old-fashioned condition (you may have heard it called “the disease of kings” due to only royalty having access to lots of meat), it’s still very much around, and growing in prevalence due to modern diets and rising obesity rates.

What makes gout unique?

Sudden, severe attacks of pain, usually at night

Redness, swelling, and warmth at the affected joint (often the big toe)

Caused by high levels of uric acid in the blood, which forms needle-like crystals

When a gout attack hits, the pain can be so intense that walking becomes nearly impossible. That kind of mobility loss, even temporarily, increases your risk of falls, especially in older adults.

Psoriatic Arthritis: When Skin and Joints Team Up

Psoriatic arthritis is an autoimmune condition that occurs in some people who have psoriasis, a chronic skin disease that causes red, scaly patches. (50) But this type of arthritis doesn’t just cause joint pain; it can also lead to fatigue, tendon inflammation (enthesitis), and even nail changes. (51)

Key symptoms include:

Swollen fingers and toes (often called “sausage digits”)

Joint pain that may be symmetrical or asymmetrical

Pitting or discoloration in the nails

Because psoriatic arthritis affects both joints and connective tissue, it can alter how you move, weaken your muscles, and lead to postural changes, all of which can challenge your sense of balance.

Reactive Arthritis: A Delayed Reaction

This one tends to fly under the radar. Reactive arthritis usually develops after an infection, often gastrointestinal or urogenital. (52) Think of it as your immune system getting a little too aggressive after fighting off a bug.

What to look for:

Joint pain, usually in the knees, ankles, or feet

Eye inflammation (conjunctivitis)

Urinary symptoms (in some cases)

Although it often resolves on its own, reactive arthritis can become chronic in some people. Lingering joint inflammation and pain can throw off your coordination and increase your risk of stumbles and falls.

How Arthritis Raises Your Fall Risk

As we have already discussed, no matter which type of arthritis you’re dealing with, whether it’s wear-and-tear osteoarthritis, autoimmune rheumatoid arthritis, or something more obscure, one thing is clear: arthritis can directly increase your risk of falling. And unfortunately, falls are one of the leading causes of injury and loss of independence in older adults. (53)

So how exactly does arthritis tip the scales against your balance? Let’s break it down with some real examples.

1. Joint Instability and Weakness

Arthritic joints are often inflamed, misaligned, or damaged. This leads to instability, like trying to walk on a wobbly ankle or a swollen knee. Over time, the muscles around those joints may weaken, either from underuse (due to pain) or from actual structural changes. That combination, weak muscles and unstable joints, is a recipe for a fall.

Common scenarios:

Your arthritic knee gives out during a step down from a curb.

A swollen ankle reduces your ability to pivot or turn safely.

Weak hip muscles make it harder to recover from a minor trip or misstep.

2. Impaired Proprioception

Proprioception is your body’s internal sense of position. It's what allows you to close your eyes and still touch your finger to your nose, or to know how far to lift your foot when walking up stairs. Arthritis can interfere with this sense, especially when the inflammation damages joint receptors responsible for sending positional feedback to your brain.

Signs of proprioceptive loss:

You feel unsure on uneven surfaces.

You catch your toes on rugs or thresholds more often.

You need to look at your feet while walking to stay balanced.

Over time, these subtle changes add up, quietly eroding your confidence and coordination.

3. The Fear-Avoidance Spiral

This part is psychological, but just as important. If arthritis makes movement painful, it’s natural to start avoiding it. You might skip your morning walks, reduce your exercise, or feel nervous about certain activities. While this might protect you in the short term, it often leads to deconditioning, a gradual loss of strength, endurance, and joint flexibility.

And guess what?

Deconditioning makes you more prone to falling. Your balance deteriorates, your reaction time slows, and your body becomes less equipped to catch itself during a stumble.

4. Real-World Stats That Paint the Picture

Still not convinced arthritis and falling go hand-in-hand? Let’s look at some numbers:

Knee osteoarthritis is associated with a two-fold increase in fall risk compared to those without knee OA. (54)

People with rheumatoid arthritis experience more frequent balance impairments and are more likely to have gait abnormalities, even early in the disease process. (45)

Older adults with arthritis are more likely to fall within a 12-month period than aged matched peers, and many fall more than once. (54)

And it’s not just about the fall itself. The aftermath can be devastating: fractures, hospitalizations, reduced independence, hospital bills, and the all-too-common fear of falling again, which can start the whole cycle over.

Slowing the Progression of Arthritis

Let’s shift gears from what's happening inside the joints to what you can actually do about it. Arthritis isn’t something you’re powerless against. Yes, it can be frustrating, and yes, it might change the way you move, but it doesn’t have to control your future. The earlier you understand what’s happening in your joints, the sooner you can take action to slow the progression and keep doing the things you love.

So, how do you stay ahead of arthritis instead of chasing it? Let’s break it down.

Early Diagnosis: Why Timing Matters

Here’s the deal, arthritis rarely announces itself with a banner in the sky. It often creeps in gradually, maybe your knee feels a little stiff in the morning, or you’re avoiding stairs without realizing why. These subtle signs are worth paying attention to.

Getting an early diagnosis can be a significant contributor to successful aging. Catching arthritis in its early stages means:

Less permanent joint damage

More treatment options

Greater chance to preserve function and independence

If you’re noticing joint pain, swelling, or stiffness that doesn’t go away, don’t tough it out, get it checked out.

Exercise and Strength Training: Movement Is Medicine

This might sound counterintuitive if you’re in pain, but trust me, movement is one of the most powerful tools you have against arthritis. (55, 56, 57)

Why? Because exercise:

Increases circulation to nourish the cartilage

Builds muscle strength to support and stabilize joints

Enhances flexibility and mobility

Boosts proprioception, which helps prevent falls

Start where you are and ease in slowly:

Strengthen supporting muscles: Especially around the hips, knees, and ankles. This helps compensate for joint instability.

Train balance regularly: Simple exercises like single-leg stands, heel-to-toe walking, or Tai Chi can improve proprioception.

Strength training deserves special mention. Strong muscles reduce joint load and improve joint alignment. Think of muscles as shock absorbers, if they’re weak, your joints take the full brunt of impact during movement.

Weight Management and Anti-Inflammatory Nutrition

Extra body weight puts extra stress on joints, especially weight-bearing ones like the knees and hips. (58) But weight loss doesn’t just ease mechanical pressure; it also reduces systemic inflammation, which plays a big role in many types of arthritis, including osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. (59)

What you eat matters, too.

A few anti-inflammatory diet basics (60, 61):

Load up on fruits and vegetables, especially colorful ones rich in antioxidants

Choose omega-3 fatty acids from fish, walnuts, or flaxseeds

Cut back on processed foods, added sugars, and saturated fats

Use spices like turmeric and ginger that have natural anti-inflammatory properties

And of course, if weight loss is your goal a subtle caloric restriction of 250-500 calories a day is a great place to start. This isn’t about restriction, it’s about giving your body what it needs to stay resilient. Even small dietary changes can have a big impact over time.

Joint Protection Strategies

Joint protection means learning smarter ways to move so you reduce stress on your joints during daily activities. Think of it like driving defensively, but for your body.

Some quick examples:

Use larger joints when possible (e.g., carry a bag with your forearm instead of fingers)

Avoid gripping things tightly for long periods

Break tasks into smaller steps with rest in between

Use assistive tools like jar openers, long-handled shoehorns, or ergonomic kitchen gadgets

Occupational therapists are great resources for personalized joint protection tips and finding interesting workarounds for everyday tasks.

Medications: A Brief Overview

There’s no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to arthritis medications, and it’s always best to work with a healthcare provider for a treatment plan tailored to your needs. But here’s a quick breakdown:

NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs): Help reduce pain and inflammation (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen) (62)

DMARDs (disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs): Slow the progression of autoimmune arthritis like RA or psoriatic arthritis (63)

Biologics: Target specific parts of the immune system involved in inflammatory arthritis (64)

Analgesics: Manage pain without addressing inflammation (e.g., acetaminophen) (65)

Every medication has pros and cons, and the goal is usually to combine meds with lifestyle changes, not rely on pills alone.

Assistive Devices: Tools, Not Crutches

Sometimes a cane, walker, or brace feels like admitting defeat, but it’s actually the opposite. These tools can give you confidence, reduce fall risk, and take pressure off your joints so you can move more freely.

Think of them as teammates, not signs of weakness. And in many cases, they’re temporary stepping stones to greater independence.

Learn a bit more about assistive devices in this comprehensive article here.

Final Thoughts: Defy the Arthritic Story

If there’s one takeaway from everything we’ve covered, it’s this, arthritis doesn’t have to write your story.

Yes, it brings about complex changes inside your joints, but understanding those changes gives you power. Power to adapt, power to move smarter, and power to stay active, mobile, and connected to the life you want.

You don’t have to change everything overnight. You just have to start.

I believe that aging well isn’t about pretending change isn’t happening, after all we can’t fight Father Time. But rather, it’s about meeting change with the right tools, knowledge, and mindset. Arthritis is only one part of the picture. With the right approach, you can keep moving forward, literally and figuratively, for years to come.

And if you feel like giving your body all the tools to fight off imbalance and falls, make sure to grab my Master Your Balance program. In this program, you’ll be lead through a customized balance journey that meets you where you are today, while making your balance invincible for the future.

References

FastStats. Arthritis. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/arthritis.htm

Toprak CŞ. Static and dynamic balance disorders in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and relationships with lower extremity function and deformities: a prospective controlled study. Archives of Rheumatology. 2018;33(3):328-334. doi:10.5606/archrheumatol.2018.6720

Duffell LD, Southgate DFL, Gulati V, McGregor AH. Balance and gait adaptations in patients with early knee osteoarthritis. Gait & Posture. 2014;39(4):1057-1061. doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.01.005

Qamar MN. Clinical Analysis of Balance Deficits in Individuals with Knee Osteoarthritis. Journal of American Medical Science and Research. 2024;3(2):28-32. doi:10.51470/amsr.2024.03.02.28

Cleveland Clinic Staff. Joints. Cleveland Clinic. Published July 18, 2023. Accessed July 26, 2025. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/25137-joints

Fox AJS, Bedi A, Rodeo SA. The basic science of articular cartilage: structure, composition, and function. Sports Health a Multidisciplinary Approach. 2009;1(6):461-468. doi:10.1177/1941738109350438

Synovitis. Cleveland Clinic. Published June 2, 2025. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/synovitis

Li G, Yin J, Gao J, et al. Subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: insight into risk factors and microstructural changes. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2013;15(6):223. doi:10.1186/ar4405

Wang Y, Wluka AE, Pelletier JP, et al. Meniscal extrusion predicts increases in subchondral bone marrow lesions and bone cysts and expansion of subchondral bone in osteoarthritic knees. Lara D Veeken. 2010;49(5):997-1004. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq034

Rice DA, McNair PJ. Quadriceps Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition: Neural Mechanisms and Treatment Perspectives. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009;40(3):250-266. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2009.10.001

Callaghan MJ, Parkes MJ, Hutchinson CE, Felson DT. Factors associated with arthrogenous muscle inhibition in patellofemoral osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2014;22(6):742-746. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2014.03.015

Arthritis. Cleveland Clinic. Published June 2, 2025. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/12061-arthritis

Arthritis - Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/arthritis/symptoms-causes/syc-20350772

Senthelal S, Li J, Ardeshirzadeh S, Thomas MA. Arthritis. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. Published June 20, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK518992/

Jafarzadeh SR, Felson DT. Updated estimates suggest a much higher prevalence of arthritis in United States adults than previous ones. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2017;70(2):185-192. doi:10.1002/art.40355

Falls and Fall Injuries Among Adults with Arthritis — United States, 2012. Published May 2, 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6317a3.htm

Osteoarthritis. Arthritis. Published January 26, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/osteoarthritis/index.html

Osteoarthritis - Symptoms & causes - Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clinic. Published April 8, 2025. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/osteoarthritis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351925

Goldring MB. Articular cartilage degradation in osteoarthritis. HSS Journal® the Musculoskeletal Journal of Hospital for Special Surgery. 2012;8(1):7-9. doi:10.1007/s11420-011-9250-z

Neogi T. Clinical significance of bone changes in osteoarthritis. Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease. 2012;4(4):259-267. doi:10.1177/1759720x12437354

Keiser M, Preiss S, Ferguson SJ, Stadelmann VA. High-resolution microCT analysis of sclerotic subchondral bone beneath bone-on-bone wear grooves in severe osteoarthritis. Bone. 2025;193:117388. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2024.117388

Sanchez-Lopez E, Coras R, Torres A, Lane NE, Guma M. Synovial inflammation in osteoarthritis progression. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2022;18(5):258-275. doi:10.1038/s41584-022-00749-9

Osteoarthritis - Diagnosis & treatment - Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clinic. Published April 8, 2025. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/osteoarthritis/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20351930

Osteoarthritis. Cleveland Clinic. Published June 2, 2025. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/5599-osteoarthritis

Branch NSC and O. NIAMS health information on osteoarthritis. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Published June 5, 2025. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/osteoarthritis

Farrokhi S, O’Connell M, Gil AB, Sparto PJ, Fitzgerald GK. Altered GAIT characteristics in individuals with knee osteoarthritis and Self-Reported Knee Instability. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 2015;45(5):351-359. doi:10.2519/jospt.2015.5540

Can changing your GAIT help osteoarthritis? Published January 17, 2025. https://www.arthritis.org/health-wellness/treatment/treatment-plan/disease-management/changing-gait-for-knee-osteoarthritis

Murphy MC, Coventry M, Taylor JL, et al. People with hip osteoarthritis have reduced quadriceps voluntary activation and altered motor cortex function. Sports Medicine and Health Science. Published online September 1, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.smhs.2024.09.005

Petterson SC, Barrance P, Buchanan T, Binder-Macleod S, Snyder-Mackler L. Mechanisms underlying quadriceps weakness in knee osteoarthritis. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2008;40(3):422-427. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e31815ef285

Zacharias A, Pizzari T, Semciw AI, English DJ, Kapakoulakis T, Green RA. Gluteus medius and minimus activity during stepping tasks: Comparisons between people with hip osteoarthritis and matched control participants. Gait & Posture. 2020;80:339-346. doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2020.06.012

Loureiro A, Mills PM, Barrett RS. Muscle weakness in hip osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Arthritis Care & Research. 2012;65(3):340-352. doi:10.1002/acr.21806

Salamanna F, Caravelli S, Marchese L, et al. Proprioception and Mechanoreceptors in Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Literature review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023;12(20):6623. doi:10.3390/jcm12206623

Mani E, Tüzün EH, Angın E, Eker L. Lower extremity proprioceptive sensation in patients with early stage knee osteoarthritis: A comparative study. The Knee. 2019;27(2):356-362. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2019.11.010

Somers TJ, Keefe FJ, Pells JJ, et al. Pain Catastrophizing and Pain-Related Fear in Osteoarthritis Patients: Relationships to Pain and Disability. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;37(5):863-872. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.05.009

Gunn AH, Schwartz TA, Arbeeva LS, et al. Fear of movement and associated factors among adults with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care & Research. 2017;69(12):1826-1833. doi:10.1002/acr.23226

Hidaka R, Tanaka T, Hashikura K, et al. Association of high kinesiophobia and pain catastrophizing with quality of life in severe hip osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2023;24(1). doi:10.1186/s12891-023-06496-6

Rheumatoid arthritis - Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/rheumatoid-arthritis/symptoms-causes/syc-20353648

Hitchon CA. The synovium in rheumatoid arthritis. The Open Rheumatology Journal. 2011;5(1):107-114. doi:10.2174/1874312901105010107

Neumann E, Lefèvre S, Zimmermann B, Gay S, Müller-Ladner U. Rheumatoid arthritis progression mediated by activated synovial fibroblasts. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2010;16(10):458-468. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2010.07.004

Kondo N, Kuroda T, Kobayashi D. Cytokine networks in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(20):10922. doi:10.3390/ijms222010922

Lovering C. The 4 stages and progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Healthline. Published June 10, 2025. https://www.healthline.com/health/rheumatoid-arthritis/stages-and-progression#stages

Rheumatoid arthritis. Cleveland Clinic. Published June 2, 2025. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4924-rheumatoid-arthritis

How rheumatoid arthritis affects more than joints. Published June 16, 2025. https://www.arthritis.org/diseases/more-about/how-rheumatoid-arthritis-affects-more-than-joints

Walsmith J, Roubenoff R. Cachexia in rheumatoid arthritis. International Journal of Cardiology. 2002;85(1):89-99. doi:10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00237-1

Toprak CŞ. Static and dynamic balance disorders in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and relationships with lower extremity function and deformities: a prospective controlled study. Archives of Rheumatology. 2018;33(3):328-334. doi:10.5606/archrheumatol.2018.6720

Metli NB, Kurtaran A, Akyuz M. Impaired balance and fall risk in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Türkiye Fiziksel Tıp Ve Rehabilitasyon Dergisi. 2015;61(4):344-351. doi:10.5152/tftrd.2015.69379

Chaurasia N, Singh A, Singh I, Singh T, Tiwari T. Cognitive dysfunction in patients of rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2020;9(5):2219. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_307_20

Hauser B, Raterman H, Ralston SH, Lems WF. The effect of anti-rheumatic drugs on the skeleton. Calcified Tissue International. 2022;111(5):445-456. doi:10.1007/s00223-022-01001-y

National Library of Medicine. Gout. Gouty Arthritis | MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/gout.html#:~:text=Gout%20is%20a%20common%20type,toe%20or%20a%20lower%20limb.

Psoriatic arthritis. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Published August 13, 2024. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/arthritis/psoriatic-arthritis#:~:text=Psoriatic%20arthritis%20causes%20inflamed%2C%20swollen,%2C%20physical%20therapy%2C%20and%20surgery.

Enthesitis and psoriatic arthritis. Published August 30, 2024. https://www.arthritis.org/health-wellness/about-arthritis/related-conditions/physical-effects/enthesitis-and-psa

Reactive arthritis - Symptoms & causes - Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clinic. Published January 25, 2022. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/reactive-arthritis/symptoms-causes/syc-20354838

Older adult falls data. Older Adult Fall Prevention. Published October 28, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/falls/data-research/index.html

Barbour KE, Stevens JA, Helmick CG, et al. Falls and Fall Injuries Among Adults with Arthritis — United States, 2012. Published May 2, 2014. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4584889/

Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center. Role of exercise in arthritis management. Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center. Published January 18, 2018. https://www.hopkinsarthritis.org/patient-corner/disease-management/role-of-exercise-in-arthritis-management/

How do exercise and arthritis fit together? Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/arthritis/in-depth/arthritis/art-20047971

Cooney JK, Law RJ, Matschke V, et al. Benefits of exercise in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Aging Research. 2011;2011:1-14. doi:10.4061/2011/681640

Weight loss benefits for arthritis. Published November 14, 2019. https://www.arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/nutrition/weight-loss/weight-loss-benefits-for-arthritis

Bianchi VE. Weight loss is a critical factor to reduce inflammation. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. 2018;28:21-35. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.08.007

Anti-Inflammatory diet Do’s and don’ts. https://www.arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/nutrition/anti-inflammatory/anti-inflammatory-diet

Anti inflammatory diet. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Published February 20, 2024. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/anti-inflammatory-diet

NSAIDs. Published January 2, 2020. https://www.arthritis.org/drug-guide/nsaids/nsaids

DMARDs. Published January 28, 2020. https://www.arthritis.org/drug-guide/dmards/dmards

Biologics. https://www.arthritis.org/drug-guide/biologics/biologics

Analgesics. https://www.arthritis.org/drug-guide/analgesics/analgesics