Research Corner: Discussing “Safe Landing Strategies During a Fall: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis” - Moon and Dr. Sosnoff

Essential Points:

Research-backed fall strategies can reduce injury risks: Moon and Dr. Sosnoff's systematic review reveals that most safe landing techniques, such as squatting and martial arts rolling, significantly reduce impact forces and injury risk during falls.

Slapping technique is ineffective for injury prevention: Despite its popularity in martial arts, the slapping technique was found to offer no benefit in reducing fall-related injuries and may even lead to hand and wrist damage on hard surfaces.

Practical application in healthcare: The findings support the integration of safe landing strategies into fall prevention programs, helping clinicians enhance patient care and reduce injury severity for those at risk of falling.

Note: This article was one of the first articles on Science of Falling, and was aimed at speaking to clinicians in healthcare. The language used reflects this, although the information is valuable to all readers.

I know research might be boring to some, but it is the cornerstone of any valid healthcare practice. Without hardworking researchers and well done, non-biased studies, we as clinicians are shooting in the dark. Reading research is not limited to overachievers; it is an activity all healthcare workers must engage in to do right by their patients. It is said that research to clinical practice integration takes roughly 17 years! (1) I don’t know about you, but I think 17 years is a godawful long time to wait for something that can help my patient now.

Now, before you continue reading, I want to give a disclaimer. Research is not my strongest academic area. For this reason, during this article I will primarily be discussing the findings of published research rather than critically reviewing it; a subtle but important difference.

Article Overview

Today’s research article is one of the most thorough I have found when it comes to the topic of actual falling mechanics. As some of you may remember from SOF Podcast #2, Dr. Goodman and I discussed the difficulties in creating high quality falling experiments and data collection. Ethically it is hard to just throw someone to the ground and see what happens. Therefore, as I said on the podcast, a flawless study on falling is hard to find.

Luckily, Moon and Dr. Sosnoff did a lot of the leg work for us in 2016 when creating their systematic review and meta-analysis, “Safe Landing Strategies During a Fall: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis”. These researchers combed through 380 research articles before boiling that down to a mere 13 studies. These chosen articles were deemed of sufficient quality and met most of Moon and Dr. Sosnoff’s proposed criteria for inclusion. These inclusion criteria are listed below:

Moon and Dr. Sosnoff’s Inclusion Criteria

Was the research question clearly stated?

Were the inclusion and exclusion criteria clearly stated?

Were the protective landing strategy and comparative strategy clearly stated?

Were the main findings of the study clearly described?

Did the selected parameters indicate impact severity?

Was the definition of initial impact well described?

Was the fall simulation condition clearly stated and uniformly applied to all participants?

Was the fall simulation protocol appropriate to reflect a real-life fall situation?

Was a sample size justification via power analysis provided?

Were potential confounders properly controlled in the analysis?

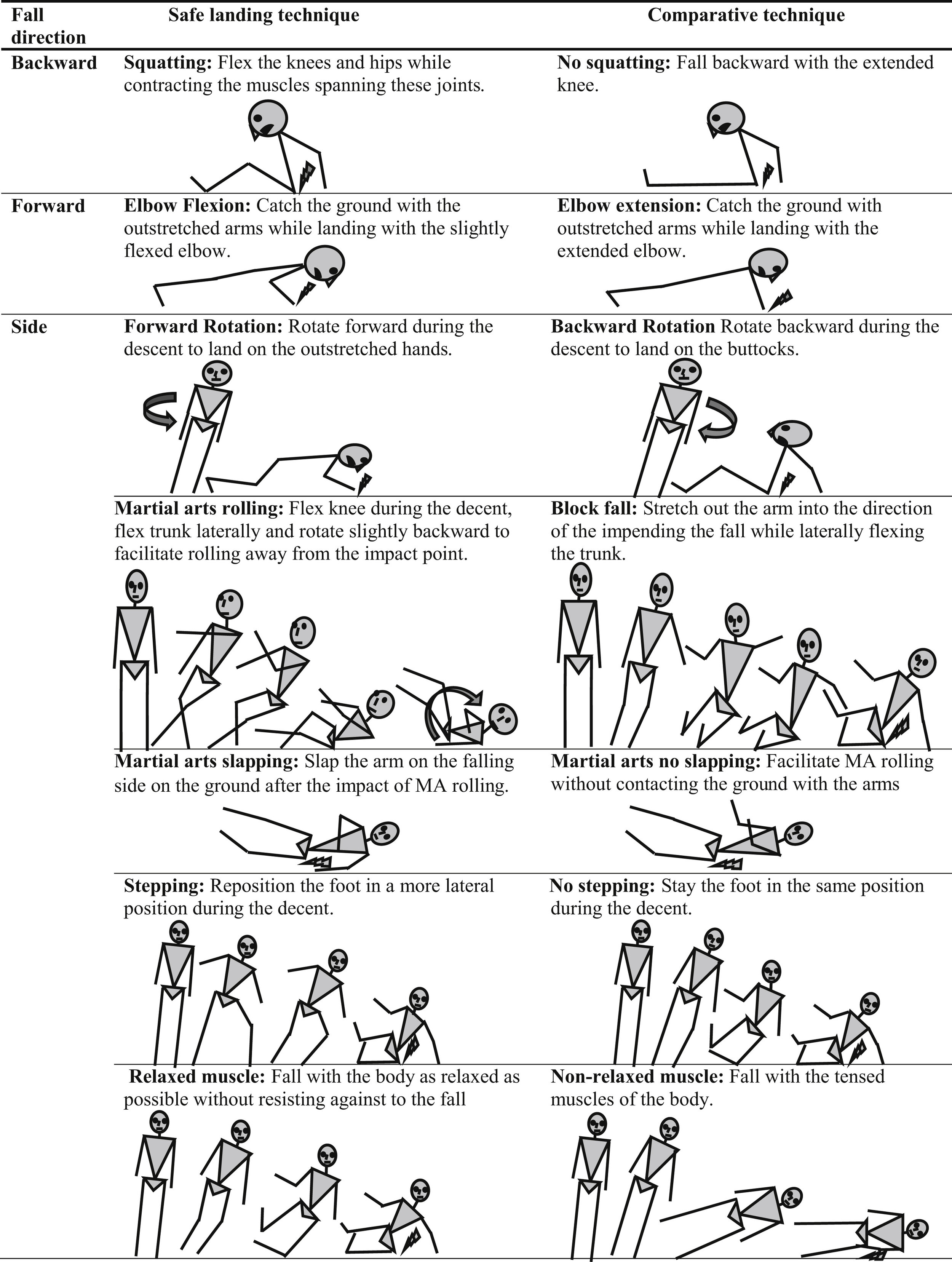

Each criterion was given a 0-2 score. Total scores were 0-20. Average selected article score was 13.5/20. Selected article scores ranged from 8-18. Within these 13 chosen studies, seven fall strategies were examined as shown in Figure 1 below: squatting, elbow flexion, forward rotation, martial arts rolling, martial arts slapping, muscle relaxation, and stepping. (2)

Figure 1: Safe landing techniques compared to non-safe techniques reproduced from original meta-analysis by Moon and Dr. Sosnoff.

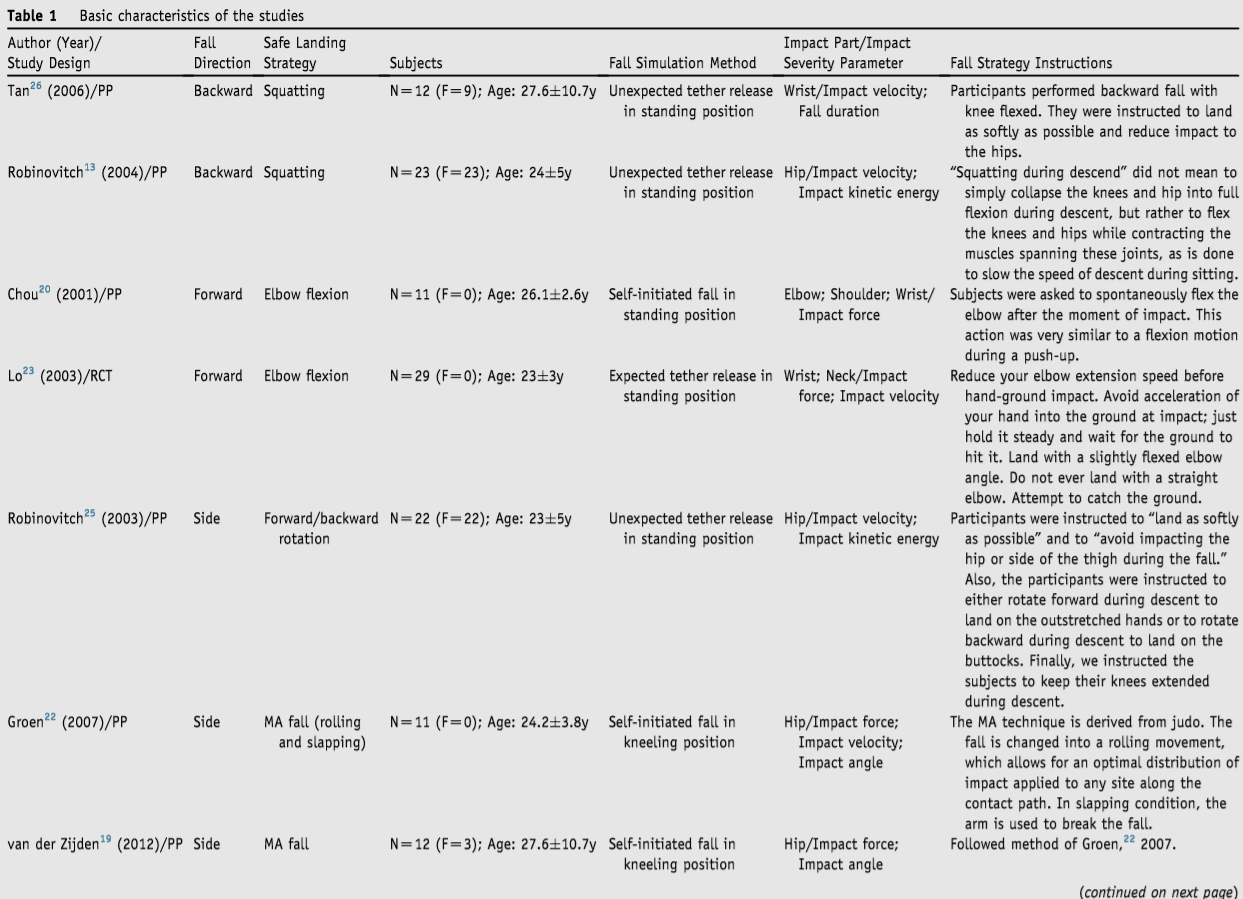

A total of 219 participants were involved in the selected studies. By sex they included 60% women and 40% men. Twelve studies had an average age of less than 30 years old (average +/- SD, 28.0+/-13.2y; range, 21-28.3y). The thirteenth study looked only at individuals 65+ (average SD, 69.5+/-5.9y). (2)

Individual Studies Overview

Table 1: Characteristics of the 13 studies chosen for analysis. Reproduced from original meta-analysis by Moon and Dr. Sosnoff.

Table 1 Continued: Characteristics of the 13 studies chosen for analysis. Reproduced from original meta-analysis by Moon and Dr. Sosnoff.

Findings

Table 2: Generalized statistical results of safe landing strategy when compared to non-safe techniques. Reproduced from original meta-analysis by Moon and Dr. Sosnoff.

Discussion

Using the findings shown in Table 2 above let us discuss what the researchers found.

The falling techniques (Figure 1) were judged on different parameters including: impact velocity, fall duration, impact energy, impact force, and impact angle. Of course, each study assessed individual parameters therefore each fall technique was not assessed on all of these criteria. Additionally, each individual experiment did not evaluate how the proposed fall technique affected the whole body, but rather selected individual body parts such as the wrist or hip. These body parts were selected for their known likelihood of injury in the type of fall chosen by researchers. Ultimately, if I had to sum up the overall findings in four words they would be, “Fall techniques work…mostly”.

Six out of the seven techniques assessed had a positive correlation with reducing factors associated with injury. Unfortunately, the ever so popular slapping technique seen in martial arts was no more useful than falling without techniques for the above-mentioned parameters. I was personally surprised by this finding because through personal experience I have found that slapping the ground after a fall can be useful as a balance guide, as well as a valid way to assist in force transfer when standing up from a roll. Of course, neither of these situations use the slapping technique as a purely shock absorbing strategy so the results of the study do make sense. I would be curious to see future studies on the slapping technique’s efficacy as a balance tool and force transfer mechanism.

If we think about it logically, it makes sense that the slapping technique does not work for the purpose of force dispersion. Often, when this technique is used, much of the fall is over before the arm and hand ever come in contact with the ground. Not only that, but most practitioners actually add in energy to create the slap (watch this video for an example), essentially defeating the purpose of trying to absorb the shock of falling. Now, in a padded environment like most martial arts, parkour, and gymnastic studios, this is fine and padding is forgiving. But if someone were to fall on concrete or hardwood flooring, I can foresee slapping the ground leading to potential hand, wrist, and elbow injuries. I could not in good conscience recommend this technique to any of my fall-risk patients.

The other six techniques on the other hand are all useful for absorbing and/or decreasing the impact forces on the body. For example, the squatting technique used during a backward fall was found to decrease both the impact velocity and impact energy at the hip. Why is this? Well, if you bring yourself closer to the ground, you subsequently have less free fall time to gain velocity. Less velocity means less impact force. Feel free to break out those dusty physics equations if need be.

The same physics were found to apply to each of the other techniques, with varying levels of effectiveness in decreasing overall forces in the effected body regions (except for the neck which showed no increase or decrease in impact velocity). So what does this mean for us health practitioners? It means falling techniques work and are an evidence based prevention/treatment modality.

I encourage you to read the original source material (here) and consider implementing some of these techniques into your plan of care for a more robust fall injury prevention plan. In the next few weeks, I will be working on fall strategy tutorials to help you bring these concepts into the clinic safely and effectively.

Citations

1. Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: Understanding time lags in translational research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2011;104(12):510-520.

2. Moon Y, MSc, Sosnoff JJ, PhD. Safe landing strategies during a fall: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2016;98(4):783-794. https://www.clinicalkey.com/playcontent/1-s2.0-S0003999316309066. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.08.460.

Thanks for reading this post on falling mechanics and safety!

Let me know in the comments below your experience with fall training and/or teaching proper falling techniques to clients/patients.

Happy falling!

Special thanks to Siobhan McConnell and Sean Thornton for editing this article